AB

Orcish Tabletop Game

This tabletop game idea is a project I have worked on as part of my master's degree at Canterbury Christ Church University.

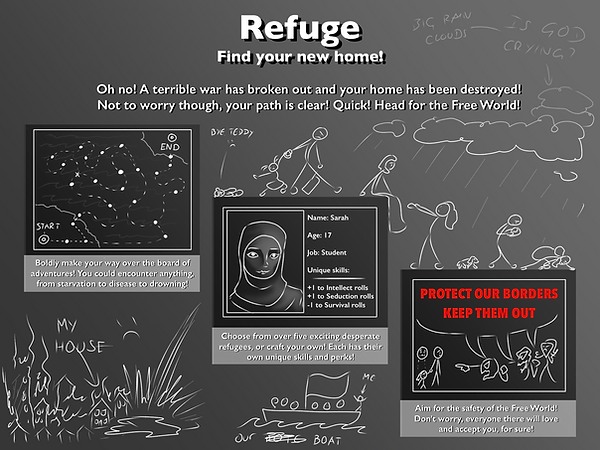

This game was centred around the theme 'protest'. I was very excited by this prompt, and I remember saying to our lecturer that I expected a lot of very angry and passionate games to be created by our class: he responded quite happily that that was exactly what he wanted!

My protest centres around refugees: the difficulty and hardship of being forced to become one, and the horrible attitudes that even people in my own family have towards them. This is a personal issue for me, as my partner is facing these exact issues: they are trying desperately to leave, yet are unable to do so. In a way, this game is catharsis for me and him.

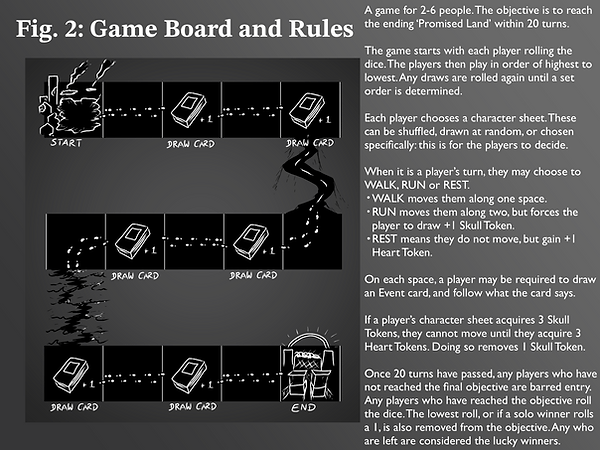

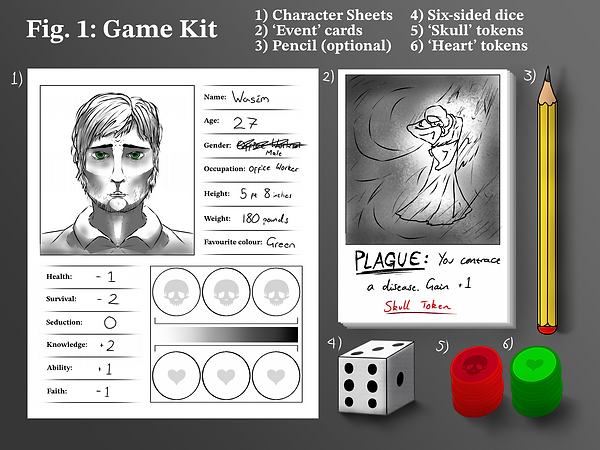

The primary inspiration for the game's mechanics was a blending of 'Monopoly' (a game which is inherently divisive and competitive in its mechanics) and 'Dungeons and Dragons' (a game which encourages teamwork and co-operation). This solidified into the idea of character sheets and event cards: the players would select a character sheet, and use numbers and modifiers from that sheet to deal with whatever an event card would require them to do. Much like Monopoly, these cards can be good or bad: unlike Monopoly, the player has a chance to avoid the bad if they are lucky enough. The reasoning behind these mechanics was that I wanted the primary experience of the game to be tense: trekking across an entire country in the hopes of arriving somewhere new for a better life is not an easy thing to do, despite the number of newspapers ranting on about how 'they're coming over here and taking our jobs!' Therefore, I wanted the experience of the journey to reflect that, even in as detached and metaphorical a way as it turned out to be.

The first iteration of this idea blatantly drew reference from real life, utilising names and fashion choices from Middle-Eastern countries. My original idea for the visual rhetoric was that it would be akin to a child's drawings, providing a key empathy with an invisible, yet omnipresent character, who the players would know nothing about except that they are suffering.

This idea in particular was inspired by a campaign by Save the Children, who created a video that imagined the life of a British child in Syria (YouTube link here). My main rationale was that providing a child-like presence would encourage greater sympathy amongst players, no matter their age or background (specifically, elderly people).

The mechanics of this first iteration were more complicated, as can be seen written out in the Fig.2 image. The rhetoric behind the mechanics for movement was that moving such large distances is slow and exhausting: trying to go too fast would therefore tire you out and make you more at risk of being hurt. There was meant to be no explicit reason for players to work together, as it was a race to reach the end, but helping each other was indeed a possibility, and if players wanted to help each other, they could. This would have been further compounded by the drawing of cards, rather like in Monopoly: these cards could help or hinder the players, potentially changing the course of the game in an instant and allowing players who may be falling behind to catch up.

On paper, the idea seemed solid.

The problems with these mechanics arose during playtesting. A player did not need to be particularly unlucky in order to become burdened by Skull Tokens, and thus unable to move at all. This, combined with the limitation for moving only one or two squares at a time, resulted in other players moving ahead at an unbeatable pace, leaving this player effectively stranded. While I considered this a very effective demonstration of my protest, as situations like this do indeed occur, it was clearly not very fun, which somewhat defeated the point of the game. If I wanted to get my message across, I was obliged to make sure that the game was at least fun to play, otherwise my players would simply not be engaged enough. I was also advised that having such an overt subject might require some...fantasy.

Dealing with this issue, I came to a point where I decided to do some serious reflection. Refugees across the world are facing genuine, awful danger; discrimination and hardship; violence and poverty. These are all things that I have been lucky enough in my life to not experience myself, and yet I want to make a game that addresses them seriously without making a mockery or stereotype out of them. This is not an easy thing to do, and getting such a game published and sold would be even more difficult. I came to the conclusion, after talking it over with my supervisor, that it would be better to remove the game from the real world, and instead use a fantasy world as an allegory. What then could I use? What classic fantasy trope is a good metaphor for real people being stereotyped and pigeonholed? I hit upon the idea almost immediately: good old Orcs.

Orcs, as a fantasy race, are hallmarked by two main features: their tusks, and their deep-seated battle-stirred bloodlust. This immediately brings to mind parallels of real world racial stereotypes, and my instant reaction was a desire to show Orcs in a new light.

If Orcs are, indeed, always at war, then surely there must be families left behind at home who are suffering from it. While the actually bloodthirsty Orcs are off doing battle, (along with the brave, the patriotic, and the foolish), their friends and children are at risk of retaliation. If their homes were destroyed, these poor Orcs would need to find somewhere else to live...somewhere safer, wealthier. The next main allegory springs to mind: the Orcs would go to the home of the Elves.

With a story settled on, I decided that I wanted to move away from the children's drawing style I was planning before, and instead, try out a style akin to graffiti. I have a lot of respect for graffiti when effort is put into it, so I looked for some proper references by going out and taking pictures where I could, and analysing some examples of Banksy's work.

I then had a go at drawing one of these unfortunate Orcs in a few ways, experimenting with how to visually compose it. I based my technique as closely as I could to actual spraypaint: using a stencil is the main key to creating sharp edges, so colours tend to be very blocky and harsh, not blended. I liked the idea that these were sprayed by the Orcs themselves in protest at their fate.

Pleased with these visual experiments, I went ahead and fleshed out a character sheet. Building on the successful mechanics from the last iteration (the ones I was told were fun), I kept the stats and modifiers to dice rolls, and decided to add two more icons at the bottom to signify any identifying information about the individual character: gender and disability. My reasoning was that, given how these Orcs are not the stereotypical warriors, there will most likely be disabled people amongst them, and so it seemed only logical to represent them. I thought that this, in turn, could be a mechanic: some event cards could have certain outcomes depending on one's gender or ability, and perhaps those in wheelchairs might move slower, but have higher stats otherwise to provide balance.

For clarity's sake: the five circles beneath the name are the five spaces for the player's Health Tokens, which represent HP. This is an improvement over the first iteration, as now, health is simply a resource. If all Health Tokens are lost, the player dies. New or excess Health Tokens can be given to other players or kept in reserve as a bartering currency, if you choose.

After I made these character sheets, I felt satisfied with the visual direction and mechanic ideas, and so I went to tackle the art of the event cards. I particularly wanted to lean more into the idea of these being spray-painted by protestors, or even by the transient Orcs themselves as they pass through ruined towns. As a result, the artwork on each card became simpler, only black silhouettes, to reflect the idea that the artist only had one can of paint, or not enough time to pull out a second.

The front of the cards I drew in red and white, thinking that I could repurpose this as an icon on the game map later if it stood out enough. Red background and white overlay creates a striking contrast, similar to the protest graffiti I found.

As I said before, these cards can be a help, a hindrance, or just an annoyance; rather like Monopoly. These cards can take away your health, give it back to you, force you to roll with (or against) a stat on your character sheet, or provide buffs/debuffs to your future dice rolls. The idea is that they are a source of constant possible upset: one can never be certain if they will maintain their lead or security.

With the cards as a source of effective chaos, the next thing I really wanted to nail was the game board, and the mechanic of Companions. While based on the typical D&D party, I wanted to specifically have travelling with others be impactful on the game, but in a way that was balanced and enjoyable for others. I had an idea, but I wanted the board first.

The board I came up with looks like thus. Players begin in 'Home', and must progress to 'Hope'. Players who lose all of their Health Tokens die and can no longer play. The 'winners' are the players who make it to Hope alive.

When rolling the dice to determine how far they travel, players can choose to travel solo, or with any number of other players. These other players become their Companions. When travelling together, all Companions roll their dice too: the numbers rolled are added together and divided by how many players are in the group. This mean number is the amount that all those players can travel, and all will travel that number at once. If an event card is drawn, it will specify if it affects only the player who drew it, or the entire group. Any of the players in a group can roll for a certain dice roll, but only one roll can be made unless specified otherwise.

This results in a dilemma for players: they can travel solo, which will allow them to travel faster on average and allow them to hoard any Health Tokens for themselves, but it also makes them more likely to draw a card which will harm them due to it requiring a roll for a low stat. Conversely, a group will travel slower and encounter more obstacles, but will be more capable of overcoming obstacles that are hurled at them. This innately speaks back to my initial rhetoric about refugees and judgement: they are people who are trying to survive, whether together or on their own. The ultimate question is what you choose to do.